Prejudice against the LGBTQ+ community could impede SC’s fight against monkeypox

Longtime feelings of stigma against the queer community might help monkeypox spread “like wildfire” through the entire state, including among heterosexual people, health officials and doctors fear.

Note: This week, I’m bringing you a story I published this morning with my colleague Holly Poag about monkeypox and how longtime discrimination toward the queer community could worsen the illness’ spread.

Joanna Haynes remembers the day one of her patients cried in her office because his best friend had died from AIDS. He didn’t even know his friend was sick.

“I asked, ‘Well, did you tell him you had it, too?’ And he said, ‘No,’” said Haynes, a social worker and the CEO of the HIV-focused clinic Careteam+ in the Grand Strand. “This is someone that he trusted with his life. That’s how stigmatizing it is in this state.”

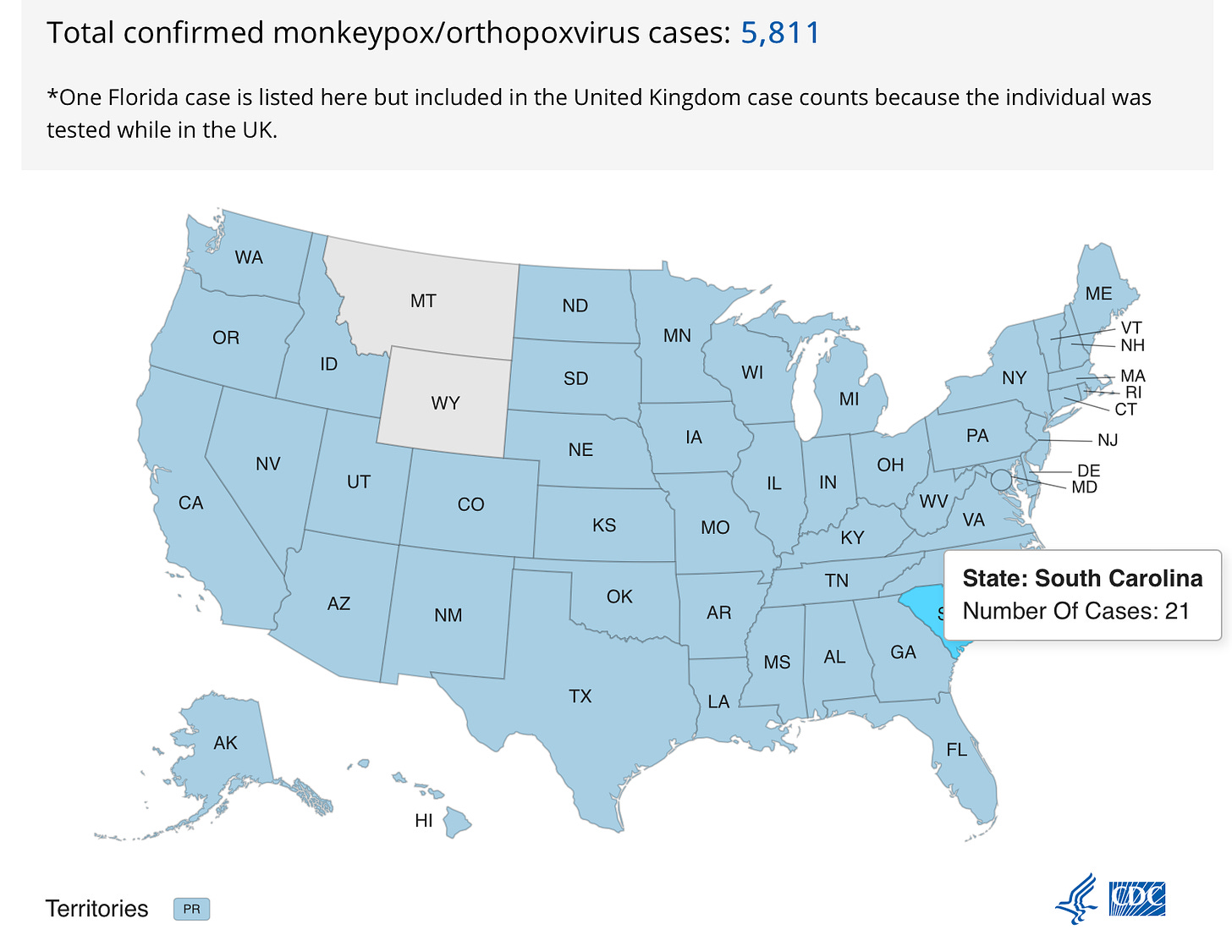

Haynes fears monkeypox, a derivative of smallpox spreading around the world right now, soon will turn into a similar tale. Men who have sex with men make up the majority of the 5,811 cases of monkeypox in the U.S., according to the latest data available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. There is already concern among medical professionals around the globe.

The World Health Organization has already declared that the virus is a problem the entire planet needs to focus on, designating it a global health emergency last week.

So far, patients in South Carolina make up just 0.36% of all cases in the country, but doctors and public health professionals in the state fear that could quickly grow. Driving those fears are two chief concerns:

If heterosexual people don’t take any precautions to protect themselves, then once the virus starts spreading outside the queer community, it will be able to spread rapidly unconstrained.

If the virus becomes considered to be a “gay disease,” then it could become harder to secure funding and support to fight it.

Unlike HIV, monkeypox is not a sexually transmitted infection, but it is spread through prolonged skin-to-skin contact and skin sores.

When infected with the virus, people may experience flu-like symptoms such as fatigue, fever and headaches followed by swollen lymph nodes and a rash. The virus isn’t deadly, but anyone who gets it could experience pain and discomfort for weeks.

“One of the things that we’ve been messaging to this community is for people to be mindful about being with a new partner and asking them if they’ve had any symptoms or looking for any rashes,” said Dr. Jonathan Knoche, a medical consultant for South Carolina’s health department.

Most infections last two to four weeks. As of Aug. 1, South Carolina has just 21 cases. However, doctors and public health workers in the state fear that number could quickly increase if the broader population doesn’t take the virus seriously.

Reminiscent of HIV

Monkeypox itself isn’t related to HIV in any biological way, but the nation may see similarities in how parts of society handle it. The virus is already viewed by some heterosexual people as a “gay disease” that they don’t have to worry about, Haynes said.

Haynes said politicians, doctors and public health workers in the ‘70s and ‘80s did the world a “grave injustice” by initially naming HIV “Gay-Related Immune Deficiency.”

“Cultures across the world have always found a group to blame,” she said. “What happened (with HIV) was that many of the groups grew in numbers of infections, while the general population heard this as a ‘gay man’s disease,’” so millions of people ignored the risks.

“I’m afraid we are doing that again,” she added. “The truth is that anyone can contract monkeypox.”

Haynes went a step further — not only can anyone become infected with monkeypox, it is almost guaranteed that sooner than later the majority of cases will be among heterosexual people.

At the same time, just like with HIV, simply “being near” gay people will not cause someone to suddenly be infected with monkeypox, said Marty Player, a family medicine doctor at the Medical University of South Carolina.

One of the most troublesome features of monkeypox is its incubation period. Haynes said the virus can take up to two weeks to show symptoms. The severity of symptoms also ranges widely. One person might only have a single monkeypox sore, while another might have hundreds of them all over their body.

“You start out with flu symptoms, so that doesn’t tell you anything. Everything seems to start with flu symptoms these days,” Haynes said. “That is followed by a rash or pimple-like lesions. You could have pimples over large parts of your body or you can have one ... and the rash looks like red ant bites.”

SC gears up public health response

Communication is key with any public health emergency, experts say. South Carolina’s Department of Health and Environmental Control said it is utilizing its partnerships with community groups and local governments as it pushes vaccination efforts for those who are at high risk and education for the broader population.

“So much of it comes back to education. In this moment, there’s just the need to encourage education around this topic, both for providers, so that they understand the virus and understand the risks,” said Chase Glenn, the director ofLGBTQ+ Health Services at the Medical University of South Carolina.

Knoche, the medical consultant for the state health department, believes that risk to the general public is low and most cases are occurring among men having sex with men. However, Knoche notes that it’s not exclusive to that population.

“We’ve seen it spread to household family members,” Knoche said. “There’s some risk there for stigma or concern (about) how it will be perceived by the general public.”

If someone is exposed to monkeypox, DHEC will interview the person to determine how long contact was, what symptoms the exposed person may be experiencing and whether they’re eligible for a vaccine.

“I feel like everyone knows about (monkeypox), but then I talk to friends I have, and they say, ‘Oh, what is that?’” Player said, showcasing how education is still important even as headlines have swirled about the virus in recent weeks. “Not everyone reads everything the way I’m reading things all the time.”

If a person develops symptoms after an interview, then health officials will order a lab test to determine whether they have contracted the virus. The state health department also has launched a website about monkeypox that alerts health care providers throughout the state about new cases and provides additional information about vaccines.

South Carolinians are eligible for the monkeypox vaccines if they are at high risk for the virus or have been a close contact with someone who has tested positive. Currently, people considered at “high risk” and eligible for the vaccine include adult men who have sex with other men and have had two or more sexual partners in the last 14 days.

The state has 1,700 vaccine doses, a small amount, but enough to ward off Player’s fear that the state would be left out altogether in favor of bigger states like New York and California.

Haynes said she was impressed with how, on a recent conference call with community health providers, officials were focused on making sure everyone had everything necessary to educate and combat monkeypox.

“There was a great deal of attention given to monkeypox,” she said. “Most of it was about teaching people to be careful and washing your hands, like with COVID, often.”

Having a website, a phone line and vaccines available to deal with monkeypox in just a few weeks, Player said that’s an astronomical effort for the state and something to be proud of.

“That speaks to some of the lessons learned in the past and the desire to be more responsive and to get it right, but that is within the constraints of the limited number of vaccines and such,” Glenn said. “Nothing’s perfect. There’s always room for improvement and for evolution in how we communicate these things.”

Player praised current messaging and marketing around monkeypox for talking about how battling it is a community effort, thereby opening doors to utilizing the resources and partnerships with LGBTQ+ community organizations that can directly reach people better than the state health department could, for example.

“This messaging is targeting that community, but it’s also an opportunity for the community to own the message and say, ‘This is what we’re doing within our community to protect our own,’” Glenn said. “It’s that balance of finding the right messaging to be really direct, that this is a segment of the community that is at highest risk right now because this is where it’s most prevalent. But also doing what we can to dispel misinformation and educate that this obviously isn’t just a gay virus.”

Community efforts

While the approach to monkeypox so far has gone well, LGBTQ+ organizations have felt the need to step up as a backstop since, historically, governmental resources to support health issues facing queer people and public health at large have been severely lacking, they say.

Dr. Smitty Heavner, who sits on the board for 864Pride, a clinical nonprofit serving the LGBTQ+ community South Carolina, said the issue of underfunding public health initiatives frequently leads to miscommunication, such as seeing HIV or monkeypox as “gay diseases.”

“There’s always a risk of someone misusing the data,” said Heavner, noting how some have used the fact that the majority of cases have been among gay and bisexual men as a weapon against that community. “As a public health scientist, and as an advocate for disadvantaged communities, as a member of a minority community — the queer community — it’s something I’m always conscious of, and we see it all the time.”

To combat the spread of incorrect information, Heavner encourages people in health care, the queer community, in the media or anyone in the position of advocacy to explain properly how monkeypox poses a risk for everyone.

The queer community, however, might be better equipped than most to deal with monkeypox, LGBTQ+ health experts said. As a result of HIV circulating for more than 50 years now, much of the community is used to having frank discussions about health and health-related behaviors. Queer-focused dating apps such as Grindr encourage users to get tested for sexually transmitted diseases and start taking PrEP, a drug that is highly effective at preventing HIV infections.

“I just feel sorry for the rest of the population when we’re hearing on the news that gay men seem to be stigmatized now about monkeypox just like they were with HIV,” Haynes said. “It’s not going to stay there. ... The next thing you know it’s spreading like wildfire.”

Direct and careful community outreach will be crucial to fighting the virus in South Carolina, Haynes said. While the queer community broadly is likely better equipped to fight monkeypox, that isn’t going to be true everywhere, especially in places that are less accepting of LGBTQ+ people, including South Carolina.

Because the virus already has a homophobic stigma attached to it, health care providers will need to work on reassuring people who have been exposed that they won’t be outed.

“I’ve been doing this in South Carolina for 17 years, and I know what a horrible stigma it is,” Haynes said. “I know that people in Williamsburg and Georgetown Counties don’t tell their primary care providers that they have HIV because they know somebody in the office.”

The vaccine, for example, is available to men who have sex with men, but those same people also have to disclose their sexuality to a stranger over the phone to get the shot. As vaccines become more available, Player suggested the state health department switch to less-invasive questions that make vaccine recipients more comfortable, such as by simply asking if they “feel they are at risk” and nothing more.

“If there is shame around it, then we know from experience that things worsen,” Player said.

Changing behaviors

One of the first steps to fighting the virus, Haynes said, is getting the vaccine for those who are eligible.

But right now, vaccine supplies are limited. Doses will become more available over time, but access to them could remain a challenge, as there is currently only one manufacturer with an approved vaccine for monkeypox, and that company is based in Denmark. The vaccine also is supposed to be a two-part series, Player said, but health officials are rationing supplies and handing out just one dose until more become available.

Haynes notes for those who do get the monkeypox vaccine, that doesn’t mean they are completely immune to the virus. Past data from Africa, where monkeypox has spent much of its time before this most recent wave of infections, shows the Jynneos shot is about 85% effective at preventing illness, according to the CDC.

“If I were a gay man, I would go get it because it’s available to me, but please don’t think that because you have a vaccine, you’re safe,” Haynes said.

With that in mind, Haynes said those most at risk should consider being more careful. Anyone who is immunocompromised should consider avoiding skin-to-skin contact with people they don’t know. For those planning to go out drinking or dancing at a nightclub, for example, this could mean avoiding dancing shirtless or dancing near other people who are.

For anyone who is sexually active, or frequently comes into prolonged contact with people they don’t know, Haynes said the most important issue to remember is that you are the only person you can be “100% sure” about. Yes, it’s always good to ask others about their activities or who they might have been exposed to, but that doesn’t mean they will tell the truth, Haynes stressed.

“This is not AIDS, and it will not kill you, but you will hate it,” Haynes said.

Anyone with concerns that they are at risk or might have been exposed can call the state health department’s CARE line, 1-855-472-3432, for more information and to make an appointment.

More than just my Love Story

Monkeypox is rousing old fears — and ways gay men care for each other. (Washington Post)

As monkeypox spreads, know the difference between warning and stigmatizing people. (NPR)

A Mini Tinder Time Capsule: A decade of ghosting, emojis, and urban legends. (The Cut)